Stanford introduced the loss of life in a press release. No trigger was given.

Dr. Berg’s query — as he and different scientists within the Nineteen Fifties and ’60s discovered extra concerning the double-helix construction of DNA — was whether or not it was doable to switch, from one organism to a different, bits of genetic data. Success would give biologists and medical researchers a completely new device package, as soon as thought of solely the realm of science fiction tales about cloning.

In 1972, he gave the reply. Dr. Berg revealed a paper in a scientific journal that exposed he had combined DNA from E. coli micro organism and a virus, SV40, linked to tumors in monkeys and transmissible to people. An uproar adopted.

Medical ethicists questioned whether or not Dr. Berg was toying with the pure order by creating what grew to become generally known as recombinant DNA. Public well being officers and others puzzled if swapping DNA may create new plagues or unleash environmental catastrophes. “Is that this the reply to Dr. Frankenstein’s dream?” later requested Alfred Vellucci, the mayor of Cambridge, Mass., residence of Harvard College and the Massachusetts Institute of Expertise.

Dr. Berg, too, had worries. He paused his experiments with SV40 and E. coli, uneasy over intersplicing the DNA of a disease-causing virus and a standard intestinal micro organism.

A 1974 letter Dr. Berg signed with 10 colleagues, revealed within the journal Science, famous “severe concern that a few of these synthetic recombinant DNA molecules may show biologically hazardous.” The letter known as for a global assembly of the scientific neighborhood to “cope with the potential biohazards of recombinant DNA molecules.”

The gathering passed off in a former chapel in Pacific Grove, Calif., in February 1975 with greater than 140 scientists from around the globe. They agreed to a common set of ideas that included limits on the forms of genes used and safeguards to maintain recombinant DNA confined to laboratories. The rules reached on the Asilomar Convention Middle had been adopted in 1976 by the Nationwide Institutes of Well being and comparable oversight teams in different nations.

Lots of the floor guidelines set by the convention have been revised or dropped as researchers developed larger understanding of genetics. But in hindsight, the worst-case pondering of the early years was merited, many researchers say.

“We needed to be terribly cautious,” George Rathmann, the previous chief govt of the biotech agency Amgen, said in 2005. “You possibly can’t put this stuff again in a bottle.”

Different individuals, nevertheless, described Dr. Berg and others as overstating the doable dangers from the gene-splicing discoveries.

“It was a mirrored image of the Vietnam period and earlier historical past,” Waclaw Szybalski, then a professor and geneticist on the College of Wisconsin at Madison, advised Science Information in 1985. “Physicists had been responsible of the atomic bomb, and chemists had been responsible of napalm. Biologists had been making an attempt very exhausting to be responsible of one thing.”

Dr. Berg stood by his warning on the time. “I couldn’t say there was zero danger,” he recalled a number of years after being awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1980. He shared the prize with two different genetic researchers, Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger.

The Nobel Committee famous how Dr. Berg’s pioneering experiment in transplanting DNA molecules “has resulted within the growth of a brand new know-how, typically known as genetic engineering or gene manipulation.”

That additionally introduced main business alternatives for what grew to become the biotech trade, starting from genetically modified crops to lots of of medicine and therapies. The early merchandise within the Eighties included vaccines for forms of hepatitis and insulin. Beforehand, insulin from animals equivalent to cattle and pigs had been utilized in human remedy.

Recombinant DNA has been utilized in monoclonal antibodies that can be utilized as a part of covid remedy, and within the newest coronavirus vaccine, Novavax, which was given emergency approval by the U.S. Meals and Drug Administration final yr.

In gene remedy, researchers are exploring methods to make use of CRISPR-based know-how — primarily genetic scissors that may insert, restore or edit genes — for circumstances attributable to genetic mutations equivalent to cystic fibrosis, Duchenne muscular dystrophy and Huntington’s illness.

Dr. Berg didn’t patent his findings, permitting pharmaceutical corporations and different researchers to advance his work.

“You probably did science,” he mentioned, “since you cherished it.”

Paul Berg was born June 30, 1926, in Brooklyn as one among three sons of a father who labored in clothes manufacturing and a mom who was a homemaker. In highschool, his curiosity in analysis was first kindled by a lady named Sophie Wolfe, who ran the science membership after lessons, he recounted.

Throughout World Warfare II, he tried to enlist at 17 to turn out to be a Navy aviator, however was turned down due to his age. He later did preliminary flight coaching whereas learning at Pennsylvania State College. He was known as up in the course of the conflict and served on ships within the Atlantic and Pacific. Dr. Berg graduated in 1948 from Penn State, and obtained his doctorate from Western Reserve College (now Case Western Reserve College) in 1952.

Dr. Berg did postdoctoral work in most cancers analysis and was an assistant professor of microbiology on the Washington College College of Drugs from 1955 to 1959, when he accepted a place at Stanford’s medical college.

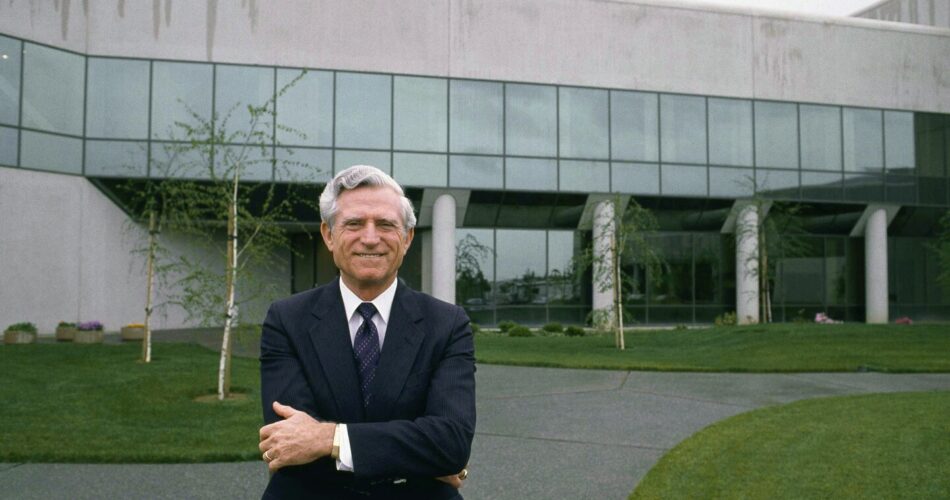

Within the early Eighties he led a marketing campaign that raised greater than $50 million to construct the Beckman Middle for Molecular and Genetic Drugs, which opened in 1989. Dr. Berg served as director of the middle till 2000.

In 2004, Dr. Berg was one among 20 Nobel laureates who signed an open letter asserting that the administration of President George W. Bush was blocking or distorting scientific proof to assist coverage selections. The letter cited omissions of local weather change knowledge or selections to disregard scientific evaluation that questioned White Home claims over Iraq’s weapons capabilities earlier than the U.S.-led invasion in 2003.

Dr. Berg married Mildred Levy in 1947; she died in 2021. Survivors embrace a son, John.

Dr. Berg gave one other contribution to molecular biology: the lingo. A recurring joke in analysis circles refers back to the second of the gene-splicing discovery. Something earlier than that’s “B.C.,” earlier than cloning.

Source link