In a year that brought about continued experimentation in gaming, as well as refinements of a style, it was arguably a throwback that charmed me more. “Return to Monkey Island,” the revitalization of a franchise that had lain dormant since 2009, was a glorious callback to a largely bygone era of point-and-click adventure games.

Yet “Return to Monkey Island” doesn’t strike me as a work of nostalgia so much as a reminder — a statement piece about the power of interactive storytelling, and a look at how much the medium has evolved since “Monkey Island” creator Ron Gilbert last directed a game in the series, way back in 1991. Gilbert was again at the helm in “Return to Monkey island” alongside longtime collaborator Dave Grossman, and what could have simply been a celebration of all things retro — see Gilbert’s own 2017 game “Thimbleweed Park” — was instead a relatively thoughtful meditation on getting older.

Set in a world of mystical pirates with unsolved treasure-hunting mysteries, “Return to Monkey Island” ultimately celebrates small moments — telling a story to your children at a park, or walking into an old neighborhood bar only to discover the regulars you knew are all gone and maybe there’s no real need to try to relive past adventures. It’s a game that prioritizes relationships, even those with foes, over big, plot-focused storytelling.

I was thankful for the chance to direct the pirate Guybrush Threepwood around the “Monkey Island” universe again. Its puzzles, most of which require Guybrush to communicate with others, allowed me time to ponder — to get to know the locals, so to speak. Interactivity here is used to forge relationships, an argument that often it’s not the stories we tell — or play — but the communities we build.

The original 1990 game, “The Secret of Monkey Island,” was a landmark in video game storytelling, a work that asked us, with a few very notable exceptions, not to solve byzantine puzzles but to use perplexing situations to build relationships, often with humor. And “Return to Monkey Island” reminded me that the reason I fell in love with video games was not for the challenge or the desire to win or compete, but for the joy of discovering a story at my own pace and of my own direction. That’s partly why, I believe, the games I gravitated toward in 2022 were those that not only prioritized narrative but did so with patience — and often with experimentation.

Many of the games I loved the most this year — “Immortality,” “Wayward Strand” and “Beacon Pines” among them — seemed to ponder the very concept of traditional narrative structure. They tinkered not only with technology, but with how we experience a story. There’s real power in that, and not just because we are active participants. We are placed in a constant state of curiousness, wondering where the storytellers are leading us and when we’re the ones driving the tale. It’s not just a game— it’s a dialogue.

“Immortality” is a love letter to cinema as well as thesis on how cinema can be reimagined.

(Half Mermaid)

“The process of writing a movie is to pull out the pieces you need and arrange them and very carefully orchestrate things,” says Sam Barlow, the director of “Immortality,” his live-action follow-up to “Her Story” and “Telling Lies.” “Immortality” is a sort of collection of multiple films. Audiences will piece together three ‘70s-era genre films, but also the behind-the-scenes clips that accompany them as well as some promotional ephemera, such as late-night television appearances. The underlying goal is to stitch together the life of a particular actor, Marissa Marcel, portrayed by Marion Gage, and to discover why she suddenly stopped working.

“When you have a game, and an audience that is interacting and expressing themselves, you don’t have to carefully keep their eye on the ball in the way you would a movie,” Barlow says. “You don’t have to worry about having 90 minutes to get the beginning, middle and end out. Just the level of curiosity and engagement they have means you can bring them and say, ‘Here is the story in a form that is sprawling and you can pick the direction and explore the pieces you would like.’ The joy I have in creating a story is giving people some of that. It allows things to become a bit more personal and earned.”

“Immortality” is at once a love letter to films but also an upending of them.

Its interactivity isn’t in picking narrative choices and directing an actor to take one action over the other. Instead, we zoom in on various pieces of the scene — an actor’s smile, a mask in the corner, a kiss or a director’s scorn — and then we jump to another scene with a connected image. The first few moments can be jarring. We’re going from an interview to a Gothic film to a sleazy detective story, sometimes to the film within the film and sometimes to behind-the-scenes moments. But after about 30 minutes we’re used to the time jumps, have a handle on each film’s exaggerated imagery and are getting to know Marcel.

In “Immortality” we uncover the mystery of actor Marissa Marcel (Manon Gage) by clicking on various pieces of an image to uncover narrative strands.

(Half Mermaid)

As the story unfolds there are hints at something more sinister beneath the surface, but “Immortality” also feels topical. It deals with workplace abuse, personal identity, labor issues and our society’s inability to often see beyond the superficial. Barlow has cited Rita Hayworth and her sculpted and shape-shifting image as an inspiration, as well as some of her off-camera turmoil. “Immortality” also aims to capture the shift from a studio-driven system to the so-called auteur-era, poking holes in the idea of a single genius along the way.

“The transition from a studio running things and controlling power to a director running things — he’s still controlling his talent and now maybe sleeping with them at the same time,” Barlow says. “When we were speaking to women working in the industry around the ‘60s and ‘70s, a recurring theme was the failure of the sexual revolution. That these freedoms have been granted, but a lot of them ultimately benefited the man.”

That it conveys such themes and ideas in a series of individualized and randomized scenes — some can be as short as a few seconds; others a few minutes — is a triumph. “Immortality” was not only the best game I played this year but the most unique, and one that argues that the narrative structure as we know it isn’t necessarily as codified as we sometimes believe.

Loose, too, in its approach to story was “Wayward Strand,” a heartwarmingly charming story about visiting with the elderly at a floating nursing home in the sky.

“Wayward Strand” allows the players to choose whose stories they will follow.

(Ghost Pattern)

“Wayward Strand” reminded me a bit of interactive immersive theater — the long-running New York production “Sleep No More” was an influence, say its creators. Early on, “Wayward Strand” throws players a curve when a character suggests that those we meet will give us tasks to complete. But those tasks never materialize.

Instead, “Wayward Strand” is solely about discovering different stories. We meet Esther, a woman who seems to have mysterious powers. Maybe. Esther may just be adept at using astrological charts to tell people what they want to hear. There’s Mr. Avery, who imagines himself a famous writer, and the grandmotherly Ida, who had a traumatic past but passes time by knitting scarves.

We hear tales of World War II, of long-lost loves and of interpersonal nursing home drama. We’re only in the nursing home during work hours, and a clock will help us maintain a routine. The clock also ensures we will miss a number of narrative strands. It’s our choice which stories we choose to follow, a decision we make by deciding who to talk to.

“We embraced the fact that players were always going to be missing things that were going on,” says Jason Baker, one of Wayward Strand’s developers with Ghost Pattern.

“We tried to keep it fairly short, so if somebody did miss something they could play it again,” Baker says. “But the vibe of the game — the themes of the game — are about being OK with only having a limited window or perspective on a particular reality and living with that and thinking about that. Fortunately, in our game, because of the setting, you’re not expecting that there’s these incredible things happening around the corner that you’re missing, even though there are interesting things happening around the corner that you’re missing. But I think players are content to spend time with characters, which was our goal.”

“Wayward Strand” reminded me of some other games I’ve only begun to scratch the surface on — the historical fiction of “Pentiment,” for instance, where our perspective on a mystery is dependent on who we talk to. But its underlying mission, that we all have a story to tell and we’re all perhaps unreliable narrators, is something uniquely suited to interactive drama, where we can select which tales to follow and investigate. Instead of exploring a narrative, we’re journeying through a fully realized world, finding our own stories within that universe.

“I think what we found in making ‘Wayward Strand,’ by the player not being able ‘solve’ the characters, it allows the characters to be fuller representations of humanity,” says Baker.

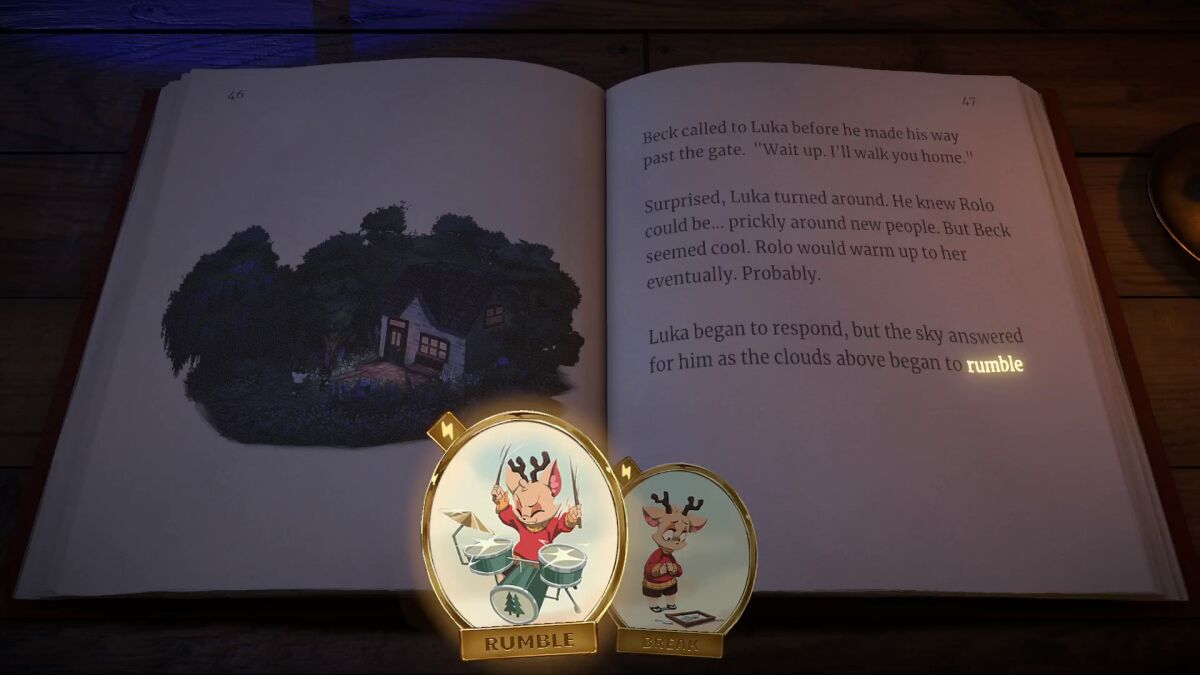

In “Beacon Pines,” we rewrite a story by discovering new words.

(Hiding Spot / Fellow Traveller )

The world of “Beacon Pines” felt slightly smaller, but no less inventive. In a fairy tale-like setting with cutesy talking animals, the game allows us to constantly remix the story. It’s slightly more traditional than “Immortality” and “Wayward Strand,” but its thoughts on how to freshen up the choose-your-own-adventure narrative structure kept me hooked. The game is set up as if we are exploring a book, only it’s one that is constantly being rewritten.

We’re tossed in a world with a number of dark underpinnings. Our hero’s mother has gone missing; his father has died. And an abandoned factory on the outskirts of town has suddenly been revived, only it’s leaking neon-green goo that can have drastic effects on everything it touches.

Our young critter wants to find his mom and get to the bottom of what’s happening in the town, but to do so he has to navigate life with a protective grandparent and a host of odd townsfolk, as well as become a master of language. As the story progresses, our actions are written down in an interactive book. The more words we discover, the greater ability we have to go back in time and change the course of the narrative.

In all these games, the puzzle is simply piecing together the story. Barlow recalls the original “Metroid,” only he replaces action with narrative.

“I always relate these games to the way a ‘Metroid’ game works,” Barlow says. “‘Metroid’ changed the game because instead of just going left-to-right, you could go left-to-right and up-and-down and you could re-traverse rooms. So the act of playing a ‘Metroid’ game is to slowly build up a mental map in your head of the planet you’re exploring. You have a deepening appreciation of rooms. You re-traverse again with a new power that unlocks a different way to navigate the room. There is an act of re-traversing a space and gaining mastery of space. Half of what is going on in a ‘Metroid’ game is the version in your head.

“Doing that, but explicitly with story content, which is what these games are doing, is really fun,” Barlow says. “You’re allowing people to unlock layers and see a piece of content that opens up a new interpretation of what you’ve already seen.”

And where we click, who we talk to or what adjectives we choose, is all driven entirely by our own curiosity. The effect is not simply exploring a world someone else created, but visiting one that feels explicitly made for us.

‘Return to Monkey Island’

Source link