from the be-careful-of-any-law-named-after-someone dept

Yesterday we wrote about how all of the terrible anti-internet bills we were worried about being slipped into the “must pass” National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) bill were, thankfully, left on the cutting room floor. However, within the 4,400 pages, there was still plenty of other nonsense added, including a variation on a bill that we had worried about almost exactly a year ago: the Daniel Anderl Judicial Security and Privacy Act.

As we noted last year, the story behind this bill is horrific, and you can understand the good intentions of the authors. But it’s pretty damn clear that the bill has serious 1st Amendment problems, and we were worried that since the only beneficiaries of the bill were judges and their families, the judges would ignore those constitutional infirmities.

The bill came about after a mentally unwell lawyer, who had practiced in front of US District Judge Esther Salas, showed up at her home dressed as a FedEx delivery person, and proceeded to shoot and kill the Judge’s son, Daniel Aderl, and shoot and injure her husband. The shooter then took his own life as well.

Obviously, that story is horrific. And it’s certainly reasonable to then be concerned about the safety of other judges. Though, when you’re carving out special protections for certain groups of people, it might also raise questions about “why aren’t we just doing a better job protecting everyone?” But, here, the form of “protecting judges” raises serious 1st Amendment issues. Because the bill allows judges to demand that certain information about them or their families be removed from the internet.

You can find the language (updated from the previous bill) starting on page 2540. And, not only do the problems we called out last year remain, the new version is even more problematic. First, it provides special powers to judges, former judges, their families (including spouses, parents, siblings, and children) as well as anyone living with the judge to demand all sorts of information be removed from the internet.

Now, perhaps you could make an argument for how some of this information should remain private. But some of it seems incredibly broad. It includes their “full date of birth.” How is it that needs to be kept private? There are also things like their “personal email address.” Which, yeah, people probably shouldn’t be making public, but what does that have to do with protecting judges from potential crazies trying to kill them?

Also, it blocks the publishing of any “information regarding the employment location” of any “at risk” individual. So, um, we can no longer publish the fact that Supreme Court Justices work in the Supreme Court building?

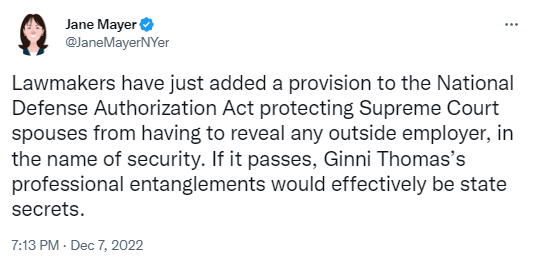

As Jane Mayer at the New Yorker notes, it’s possible this would allow, say, Ginni Thomas to effectively shield some of her many (questionable) professional entanglements:

This is exactly why we called out some of the 1st Amendment concerns with the bill last year — and the concern that judges will ignore it because they’re the sole beneficiaries of the law.

But, the new version of the law also changed in a sneaky way to more or less slip in an attack on Section 230. First, the law will apply to an “interactive computer service” as defined in Section 230, effectively making it clear that they’re using this to cut a slice off of 230:

It then allows the protected individuals (judges and their families) or someone they designate as an agent to issue takedown demands:

IN GENERAL.—After receiving a written request under paragraph (1)(B), the person, business, or association shall—

(i) remove within 72 hours the cov2 ered information identified in the written request from the internet and ensure that the information is not made available on any website or subsidiary website con6 trolled by that person, business, or associa7 tion and identify any other instances of the identified information that should also be removed; and(ii) assist the sender to locate the cov11 ered information of the at-risk individual or immediate family member posted on any website or subsidiary website controlled by that person, business, or association.

Again, given the story of what happened to Judge Salas, you can understand the thinking here, but it appears little to no thought has been given to how this can be abused. So, just to use the Ginni Thomas example, it appears that Thomas can designate an agent to demand all sorts of potentially newsworthy information about herself be removed from any website, with a 72-hour cut off.

So while it technically does not modify Section 230… it really kinda does. Because Section 230 currently says that websites can’t be held liable for third party content, which this bill clearly covers. As Section 230 biographer Professor Jeff Kosseff notes, while this “does not provide an explicit exception to 230… it does create a rule of construction that at least implies an exception for platforms that do not fulfill requests to remove covered info.”

That means, if this goes through, you can fully expect other similar “exceptions” to be written into other laws as well. And, once again, we’re left with the same sort of moderator’s dilemma questions that come up whenever you chip away at Section 230. This bill, like any law that allows for the removal of content (see: DMCA), will be abused to hide perfectly reasonable, legitimate, and potentially newsworthy information.

Keeping judges safe is obviously important. But we shouldn’t throw out the 1st Amendment (and Section 230) because one deeply unwell individual killed someone. We can invest in better mental health treatment. We can institute background checks for gun purchases. Those are the kinds of things that protect everyone.

Tossing out the 1st Amendment so that judges and their families can hide information about themselves online seems like a real problem.

Companies: 1st amendment, at risk, daniel anderl, esther salas, free speech, ginni thomas, intermediary liability, judges, liability, ndaa, protecting judges, section 230