The Russian government might pursue several different lines of cyberattacks, including targeting the “weaker links in NATO,” in retaliation for Western sanctions, said Warner (D-Va). He expressed concern that political aggression could escalate and that Russian cyber criminals could be unleashed on the West — a tactic that could give the Kremlin plausible deniability for attacks carrying economic consequences for the United States and its allies.

“It’s a good way to give us the finger without creating a bigger strategic problem for the Russians,” said Jim Lewis, a cybersecurity expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Attacks impacting the U.S. or NATO allies raise a “whole host of questions,” Warner said. “We’re in uncharted territory.”

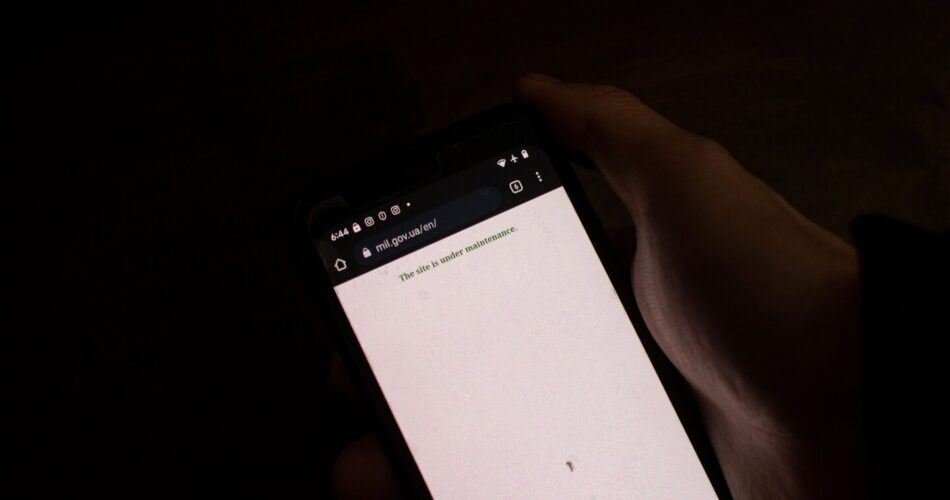

Russia is among the countries that have put the most resources behind developing and using formidable hacking tools against rival nations, a potent threat as it launches a broad military assault. On Wednesday, cyberattacks disrupted the websites of several Ukrainian government agencies, according to Ukrainian officials, and last week the White House attributed attacks on government sites and banks to the Russian military spy agency GRU.

These attacks have not yet had major ramifications outside of Ukrainian borders. The destructive software deployed during the Russian attacks in Ukraine was also found in Lithuania and Latvia, but only at organizations with a major Ukraine presence, according to security firms tracking the data-wiper.

The Symantec security division of Broadcom said Thursday that the malware, which was digitally signed to allow deeper penetration in computers, was aimed at financial, defense, aviation and tech services industries. At least in some cases, it came camouflaged as ordinary ransomware seeking a payoff.

The digital incursions outside of Ukraine appeared to be spillover, rather than a concerted effort to attack allies in NATO, said Symantec research leader Vikram Thakur and Dmitri Alperovitch, former chief technology officer at CrowdStrike.

Russia’s use of cyber weapons could create new dilemmas for NATO, which in 2021 said it would weigh “on a case by case basis” whether a cyberattack would trigger its Article 5 collective defense principle, which establishes that an attack against one ally an attack against all allies. The article was invoked for the first time after the 9/11 attacks on the United States, setting the stage for NATO allies to lend the United States military support.

“Phase one is spillover Russian attacks against Ukraine, phase two would be Russian and cyber criminals attacks against the West or NATO nations that have the least amount of cyber defenses,” said Warner (D-Va.).

Alperovitch said he anticipated some cyber response to U.S. sanctions soon. If the latest round of sanctions takes a considerable toll on the Russian economy, such counter-measures could expand to include attacks that would hurt U.S. financial transfer systems and markets, he said.

The Cybersecurity Infrastructure and Security Agency has created a website with guidance for companies, which warns of “the potential for the Russian government to consider escalating its destabilizing actions in ways that may impact others outside of Ukraine.”

“While there are not any specific, credible, cyber threats to the U.S., we encourage all organizations — regardless of size — to take steps now to improve their cybersecurity and safeguard their critical assets,” a Department of Homeland Security spokesperson said in a statement.

In the past years of tensions with its neighbor, Russia has used Ukraine as a proving ground for some of its techniques. In 2015 and 2016, it crossed a line by knocking out power to many residents during the dead of winter. And in 2017, it unleashed one of the most costly cyber attacks in history, NotPetya, with fake ransomware that wiped data and programs from machines in Ukraine and elsewhere, causing billions of dollars in losses.

The swift spread of NotPetya beyond Ukraine’s borders underscores concerns about the potential global impact what may initially appear to be a targeted attack, according to Warner.

“That kind of unbridled attack against Ukraine…I am still worried, that if it takes place it won’t respect geographic boundaries,” he said.

That history, and what the White House has called an unprovoked kinetic attack on Ukraine, has raised fears that Russia could damage utilities or other critical infrastructure in the West in the weeks to come.

“This is an actor that is clearly happy crossing norms and boundaries,” said Sergio Caltagirone, vice president at industrial control security specialist Dragos Inc. “Expecting an electric company in the U.S. with 5,000 employees to protect against the country of is a ridiculous position to put anyone in. If there is spillover in NATO or the U.S., which are the highest areas of concern for industrial control attacks, we’re looking at a very dramatic kind of outcome.”

While Russia did not unleash the full extent of its cyber weapons in Ukraine in the early hours of the invasion, Warner said it’s possible it could escalate its attack in the coming days, as Ukrainians resist its advance. He’s concerned any Russian efforts to target Ukraine’s critical infrastructure could impact power grids and other systems in neighboring countries.

“The fact that those networks are sometimes interconnected across borders: I do have a real fear that inadvertently this could shut off the power in part of Poland or other critical infrastructure, and you could have loss of life, whether it be Polish citizens or NATO troops who are trying to help refugees,” he said.

Source link