The grisly 17-second clip was recorded by videographer Adam Ward on Aug. 26, 2015, as he and Parker were fatally shot by a disgruntled former colleague while reporting near Roanoke. Broadcast live, the horrifying footage quickly went viral, viewed millions of times on Facebook, YouTube and other sites. Six years later, it still gets tens of thousands of views, despite the efforts by Parker’s father, Andy, to eliminate the clips from the Internet.

Now, Andy Parker has transformed the clip of the killings into an NFT, or non-fungible token, in a complex and potentially futile bid to claim ownership over the videos — a tactic to use copyright to force Big Tech’s hand.

“This is the Hail Mary,” Parker said, an “act of desperation.”

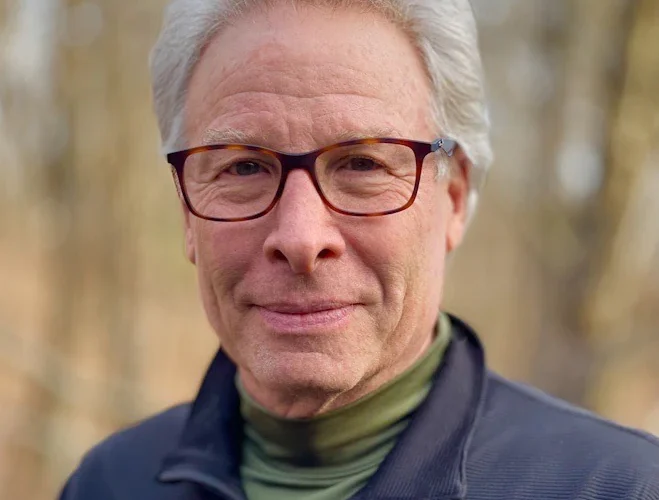

While Facebook and YouTube say they have taken down thousands of clips of the murders, dozens have remained on the platforms. Through the years, Parker has deployed a range of strategies for erasing the stragglers, enlisting a fleet of allies to search and flag the videos and filing complaints with federal regulators. Last month, he launched a congressional campaign focused partly on holding social media companies accountable for the spread of harmful content on their sites.

Under current law, the platforms are largely shielded from liability for the content of posts by their users. But the platforms may still be subject to copyright claims if they don’t remove infringing content, and experts say a lawsuit alleging the video is copyrighted material could offer Parker a more effective path to getting it taken down.

“For victims of horrific images being distributed on the Internet generally, unfortunately and inappropriately copyright does end up being an effective tool,” said Adam Massey, a partner at C.A. Goldberg, PLLC, a prominent law firm that has advised Parker.

Families of shooting victims have frequently relied on copyright law to get results. Lenny Pozner, whose son Noah Pozner was killed in the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in 2012, has filed hundreds of copyright claims to get pictures of his son taken down from websites spreading conspiracy theories about the deadly Sandy Hook shooting. Copyright, Pozner has said, is a more effective tool than relying on the platform’s policies against hoaxes, for instance, which can often be opaque and unevenly enforced.

Copyright also has been a useful tool for victims of nonconsensual pornography, where the mere threat of legal action can be more effective than petitioning platforms, Massey said.

“In the early days, there were folks, mostly women, who were having to register their copyrights of their nudes with the government to try and get them taken off websites …” he said. “Part of the logic is that, if you have the copyright, you can more effectively advocate with the platforms for their removal.”

Parker does not own the copyright to the footage of his daughter’s murder that aired on CBS affiliate WDBJ in 2015. But in December, he created an NFT of that tape on Rarible, a marketplace that deals in crypto assets, in an attempt to claim copyright ownership of the clip. That, he hopes, will give him legal standing to sue the social media companies to remove the videos from circulation.

NFTs are unique pieces of digital content logged as assets using blockchain, the same technology that powers cryptocurrency. Over the past year, NFTs have exploded in popularity as people have rushed to buy, sell and trade NFT collectibles created from fine art, crude memes and even an animated version of Melania Trump’s hat.

Under existing laws, copyright holders are exclusively able to reproduce, adapt or display their original work, unless they grant another party permission to do so. Intellectual property lawyers said the concepts should hold true for NFTs.

But the rush to transform the vast swath of content circulating freely online into NFTs has unearthed ownership disputes. The blockchain records a permanent history of every transaction on a decentralized server, theoretically making it easy to track the ownership. Amid the buying blitz are situations like Parker’s, where an NFT holder has created a duplicate, crypto-certified version of a piece of content, leaving two purported owners of the same media.

Experts say the case law on NFT ownership is still in the early stages of development and has already prompted a number of copyright disputes. In one instance, a 12-year-old coder sold an NFT collection he created of pixelated whale images called “Weird Whales” for over $300,000. But according to Fortune magazine, users accused the project of copying a separate image the coder does not appear to own to create his NFT. The boy’s father told the BBC he’s “100 percent certain” his son has not broken copyright law and has asked lawyers to “audit” the project.

WDBJ parent company Gray Television owns the copyright to the original footage of the shooting and has declined to hand it over. Kevin Latek, chief legal officer for Gray Television, contends that the footage does not depict Alison Parker’s murder since the “video does not show the assailant or the shootings during the horrific incident.”

In a statement, Latek said that the company has “repeatedly offered to provide Mr. Parker with the additional copyright license” to call on social media companies to remove the WDBJ footage “if it is being used inappropriately.”

This includes the right to act as their agent with the HORN network, a nonprofit created by Pozner that helps people targeted by online harassment and hate. “By doing so, we enabled the HORN Network to flag the video for removal from platforms like YouTube and Facebook,” Latek said.

Parker and his legal advisers say that without owning the footage, the usage license is of little use when it comes to forcing social media companies to remove clips of the killings. By leaning on the license as his legal basis to create an NFT of the copyrighted WDBJ footage, Parker hopes to bypass the standoff with Gray Television and take up his case again directly with the social media platforms.

Even if Parker’s NFT gambit works, getting the copyrighted footage taken down would only be half of the answer. The NFT doesn’t cover a separate clip of the murder taped by the shooter, Vester Lee Flanagan, a former WDBJ reporter who was fired in 2013. Some platforms, like YouTube, have been more rigorous about removing Flanagan’s footage, in accordance with the platform’s policy of banning videos of violent events when filmed by the perpetrator.

“We remain committed to removing violent footage filmed by Alison Parker’s murderer, and we rigorously enforce our policies using a combination of machine learning technology and human review,” YouTube spokesperson Jack Malon said in a statement.

Under YouTube’s policies, the platform may prohibit younger users from viewing a violent video instead of removing the post if it includes “sufficient” educational context, such as in a news report, Malon said.

Facebook bans any videos that depict the shooting from any angle, with no exceptions, according to Jen Ridings, a spokesperson for parent company Meta.

“We’ve removed thousands of videos depicting this tragedy since 2015, and continue to proactively remove more,” Ridings said in a statement, adding that they “encourage people to continue reporting this content.”

But years later, videos uploaded in the days immediately after the shooting remain online.

A review by The Washington Post found nearly 20 posts on Facebook containing a version of the murder footage, including some filmed by the gunman. While some had only a few hundred views, others had tens of thousands, including one with over 115,000 views and over 1,000 likes that had remained up since August 2015. Facebook removed all of the videos after they were flagged by The Post.

To this day, Parker hasn’t watched any of the footage. “I can’t. I can’t,” he says.

Aderson Francois, a Georgetown Law professor who represented Parker in his complaints to the Federal Trade Commission against Facebook and YouTube, called it “indescribably awful” to not only have to report the videos one-by-one, but also to read and listen to “the conspiracy theories that folks are spinning” around the murders, including that it was faked or part of campaign to seize people’s guns.

“When you watch them, you have to step away after a while,” Francois said. “After a while, it causes me to have nightmares, to have sleepless nights, to have flashbacks.”

Parker did not inform Gray of his intent to make an NFT of the footage before minting it. Asked for comment on Parker’s NFT, Latek said, “While we have provided usage licenses to third parties, those usage licenses do not and never have allowed them to turn our content into NFTs.”

Rarible, the marketplace where Parker created the NFT, prohibits content that violates copyright, according to its terms of service. On its website, the company says it will “immediately remove” content that may violate copyright. Rarible did not return a request for comment on Parker’s NFT.

Moish Peltz, an intellectual property lawyer who specializes in blockchain, crypto and NFTs, said the digital tokens could pose unique tests for how copyright principles apply in cases with extenuating circumstances.

“We’re not rewriting copyright law here, but I do think that NFTs create a new context where there just aren’t legal decisions as to how they should apply in certain cases,” Peltz said, adding that “some edge cases … raise some interesting questions.”

Parker is hoping his situation will be one of those edge cases. Amid the dispute, his relationship with Gray Television has deteriorated, and the company has hired a communications firm, Breakwater Strategy, to deal with matters related to Parker.

In his statement, sent to The Post by a Breakwater Strategy representative, Latek accused Parker of making false statements about the company and of leaving “threatening and harassing voicemails for Gray Television employees at all levels.”

Parker concedes that his NFT gambit places him in “uncharted waters.” But, he said, “in lieu of co-copyright, this is the only thing that we can do.”

Source link