5G mobile phone emissions won’t harm airliners, Britain’s Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) has said, dampening down excitement in the US about mobile masts interfering with airliners’ altimeters.

In December the US Federal Aviation Authority (FAA) issued warnings about the 5G C-band frequencies used for mobile phones, saying the 3.7-3.98GHz band used by phone masts clashed with airliner radio altimeters.

Warnings duly went out telling airlines to watch out for problems, followed by two prominent US mobile network operators delaying the rollout of the C-band.

Radio altimeters (radalts for short) calculate the height of an aeroplane above whatever’s directly underneath it. Conventional pressure altimeters give a reading relative to a pilot-selected pressure setting, typically one relating to height above mean sea level. Radalts feed into all kinds of systems, including the Ground Proximity Warning System (GPWS; it’s the one that shouts “pull up!” when airliners get too low) and similar safety systems, including autoland in bad weather.

Yet a couple of weeks prior to that delay, the CAA said there was nothing to worry about. In a safety bulletin issued on 23 December, the regulator told pilots: “Conversations with other [national aviation authorities] has established that there have been no confirmed instances where 5G interference has resulted in aircraft system malfunction or unexpected behaviour,” while cautiously adding: “Past performance is not a guarantee for future applications.”

As we previously reported, the US concerns focus on an October 2020 report from the Radio Technical Committee for Aeronautics. Its analysts carried out a simulation of bleed-through from 5G bands to radio altimeter bands, relating that to potential mobile mast positions beneath airport approach paths.

Radio altimeters operate between 4.2GHz and 4.4GHz, according to a presentation [PDF] delivered to the International Civil Aviation Organisation in 2018 summarising then-current risks to radalts, which didn’t include mobile phone spectrum. This is separated by a few hundred MHz from the radio altimeter band. So what’s going on here?

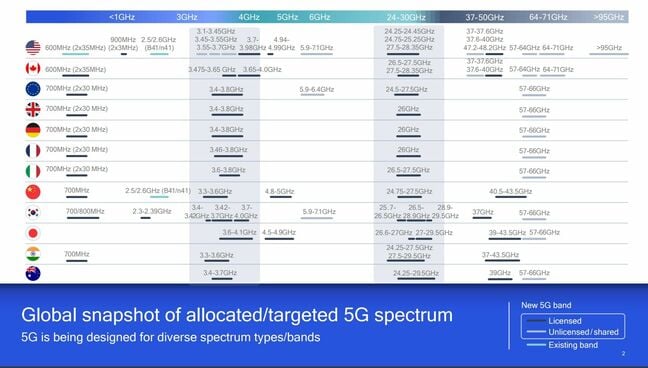

A Qualcomm slide showing 5G spectrum allocations worldwide in December 2020. Click to enlarge. The full PDF presentation is here.

Ollie Turner, a spokesperson for the UK Civil Aviation Authority, told The Register in a prepared statement: “There have been no reported incidents of aircraft systems being affected by 5G transmissions in UK airspace, but we are nonetheless working with Ofcom and the Ministry of Defence to make sure that the deployment of 5G in the UK does not cause any technical problems for aircraft.”

Similarly, the EU Aviation Safety Authority (EASA) said in a bulletin rejecting a Canadian radio altimeter directive resembling the FAA’s 5G warning: “EASA has not been able to determine the presence of an unsafe condition but continues to closely coordinate with the affected design approval holders before deciding if mandatory action is warranted.”

It appears regulators on this side of the Atlantic aren’t worried about the gap between the Europe-wide 3.4-3.8GHz 5G spectrum allocation and the 4.2-4.4GHz radalt band. The reason for the FAA (and US pilot trade union ALPA’s) caution would appear to be fears of mobile networks’ traffic from the top edge of 3.98GHz bleeding into the neighbouring band.

The FAA has also said that 5G power levels are significantly higher in the US than elsewhere. The body pointed out that in the US, “even the planned temporary nationwide lower power levels will be 2.5x higher than in France” (1585 Watts vs 631 Watts).

Point ‘n’ zap

Gartner analyst Bill Ray (once of this parish) told The Register the difference in power levels is part of the problem, with the other being that nobody knows just how good radio altimeters’ RF filters are.

“If you’re the US military and you over-specify (and overspend) on everything then you’re probably going to be fine,” he said, pointing out that radalts can be fitted to private light aeroplanes too – and light aircraft are subject to less strict maintenance rules than commercial airliners.

“The problem is that no one has ever done a comprehensive study of how good the filters on altimeters are, so no one knows how bad the problem will be.” On top of that, there’s a potential problem with directional 5G (or indeed any mobile phone) signals.

“MIMO uses beamforming to direct a radio signal at the receiving mobile phone, so in theory signals should not be directed at the aircraft, except that lots of people forget to turn their phones off when flying so we have to assume that a 5G radio beam will (at some point) be directed at an aircraft coming in to land,” said Ray.

Indeed, this is one of the reasons airline passengers are told to turn their phones off during takeoff and landing.

In practice a radio altimeter failure could range between inconvenient and very troublesome. An A320 pilot consulted by The Register told us a radalt failure at a late stage of an approach to land could, according to aircraft manuals, cause “untimely FLARE and THR[UST] IDLE mode engagement,” which he characterised as potentially catastrophic in bad weather – but not difficult to cope with if the airliner’s crew can see the ground.

“My opinion? No one knows for sure and everyone is using fancy words to hide it,” shrugged our tame pilot. Perhaps he’s got a point. ®

Source link