The judge overseeing an age-discrimination case against IBM has denied the IT giant’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit, citing evidence supporting plaintiff Eugen Schenfeld’s claim that CEO Arvind Krishna, then director of IBM research, made the decision to fire him.

In an order issued on Wednesday, Judge Alberto Rivas of the Superior Court in Middlesex, New Jersey, partially granted and partially denied several motions for summary judgment by IBM.

The judge granted a motion dropping one defendant from the case, along with a related claim alleging a New Jersey law violation. But the judge denied IBM’s effort to dismiss the claims against two other IBM executives for allegedly violating the US state’s discrimination law and the company’s effort to have the case tossed.

The lawsuit [PDF] centers around a 2018 staff reduction referred to as Project Concord that led to the firing of former IBM research scientist Eugen Schenfeld at the age of 60.

Project Concord is one of several staff reductions with similar names, like Project Baccarat and Project Ruby, that are alleged to have focused unlawfully on older workers.

According to a 2018 report from ProPublica and Mother Jones, IBM shortly after Ginni Rometty became CEO in 2012 embarked on a plan to fire older workers, which is a violation of US law. In 2020, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) found that “top-down messaging from [IBM’s] highest ranks directing managers to engage in an aggressive approach to significantly reduce the headcount of older workers to make room for early professional hires.”

These allegations have led to dozens of age-discrimination lawsuits against IBM, and attorneys involved argue [PDF] that the number of potential plaintiffs amounts to almost 13,000 former employees who left IBM since 2017 after the age of 40.

IBM has consistently denied any wrongdoing, has settled age-discrimination claims without admitting guilt, and recently took the unusual step of having Chief Human Resources Officer Nickle LaMoreaux publicly assert that the corporation doesn’t have a policy of age discrimination. Following media reports about documents made public in a different age-discrimination claim, Lohnn v. IBM, LaMoreaux published a statement claiming “there was (and is) no systemic age discrimination at our company.”

The judge’s order [PDF] in Schenfeld v. IBM describes how Schenfeld was not initially part of the group of people slated to be laid off in Project Concord, but that the intervention of an executive put his name in play.

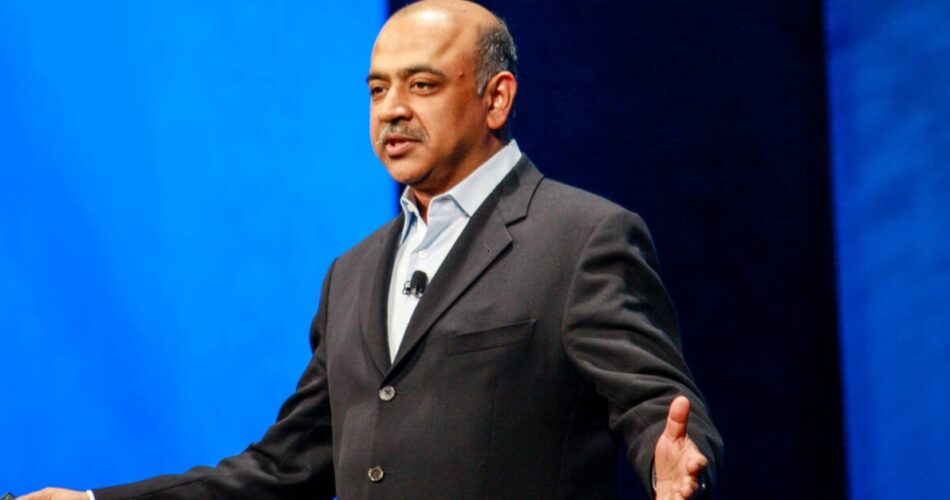

When Varun Gupta, then director of human resources for research, met Krishna, head of research at the time, to review a preliminary list of employees to terminate, it’s claimed that following the meeting, Gupta sent an email to Sophie Vanderbroeke, then COO of research, indicating he wanted to add Schenfeld to the list. Schenfeld claims Gupta indicated Krishna sought to have Schenfeld added to the termination list.

IBM may have hoped that new leadership, namely the appointment of Arvind Krishna as CEO in 2020, the spin-off of its global technology services division as Kyndryl, and other structural changes would allow the company to avoid dealing with allegations from the Rometty regime. That becomes more difficult if Krishna gets roped into discrimination claims. Tying top executives to these matters makes it harder to argue that there was no systematic, company-wide plan to de-age IBM’s workforce.

IBM emphatically denied Schenfeld’s allegations when The Register initially reported on the case.

“Plaintiffs’ briefing has falsely described Arvind Krishna’s involvement in this matter,” a spokesperson for Big Blue told The Register. “As head of a business unit at that time, Arvind was aware of individuals who may be separated from the company but did not make any selections. Plaintiff’s mistruths do not change the facts.”

We asked IBM whether it wished to comment further but we’ve not heard back.

Nonetheless, the judge, in his explanation for his denial of IBM’s motion for summary judgment, said that despite IBM’s assertion that Zachary Lemnios, then president of the research division’s science and technology group, pushed for Schenfeld’s ouster, “there is evidence in the record that supports an inference that the decision to terminate [Schenfeld] was made by Arvind Krishna following a meeting between Krishna and Gupta, then director of human resources.”

The judge’s decision to allow the case to move forward does not establish that Krishna actually asked to have Schenfeld fired. Rather it indicates there’s enough evidence that a plausible argument can be made at trial to determine whether that actually happened.

Schenfeld’s attorney, Steven Cahn from New Jersey-based law firm Cahn & Parra, told The Register that he is looking forward to having the case advance to trial where evidence can be presented. ®

Source link