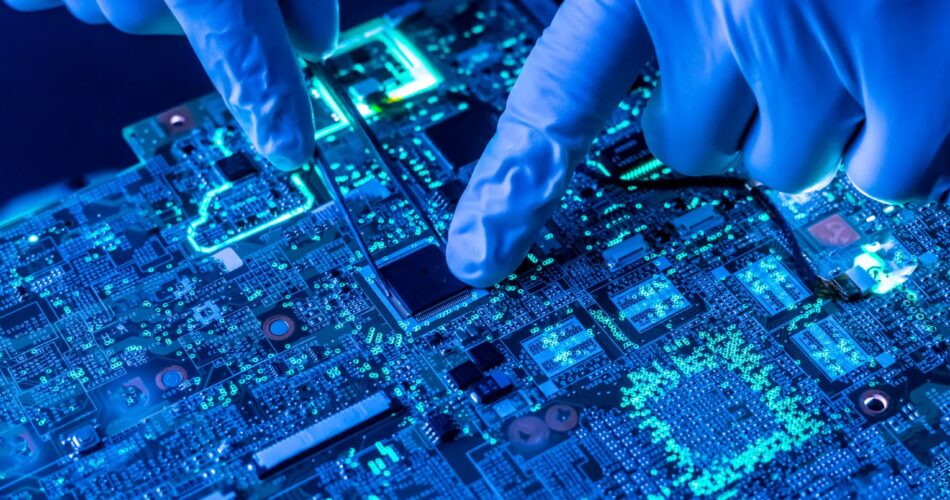

Why it matters: The Ukraine crisis has sparked concerns on the stability of the global semiconductor supply chain. For now, chipmakers say there’s no immediate risk thanks to raw material stockpiling and diversified procurement strategies, but they are looking for alternative suppliers to avoid potential disruptions in the future.

By now it’s no secret that Russia launched a full-scale attack on Ukraine earlier this week, which prompted several countries to consider new sanctions on the former. As local factories closed on Thursday, some in the tech and auto industries worry about the potential impact on the global supply chain.

According to Techcet analysts, both countries supply significant quantities of materials needed for making chips on pretty much any process node. Specifically, Ukraine supplies over 90 percent of the semiconductor-grade neon used by the US, while 35 percent of the palladium imported to the US is from Russia. Manufacturers may have stockpiles of certain materials and gases required and source them from various suppliers, but that doesn’t mean they’re entirely protected from disruption.

While the geopolitical shock caused by the ongoing military conflict is undeniable, chipmakers are trying to downplay fears that it will worsen the global shortage of chips. According to the Semiconductor Industry Association (SIA), Russia only accounts for 0.1 percent of global chip purchases, and its incursion into Ukraine doesn’t pose any immediate supply disruption risks, as the industry relies on a “diverse set of suppliers of key materials and gases.”

Companies like ASML — who makes EUV lithography equipment — and memory manufacturer Micron rule out the possibility of major disruptions in the short term, but they are currently exploring alternative sources of noble gases for production needs. Intel, GlobalFoundries, SK Hynix, United Microelectronics Corp. and ASE Technology had similar statements on the matter.

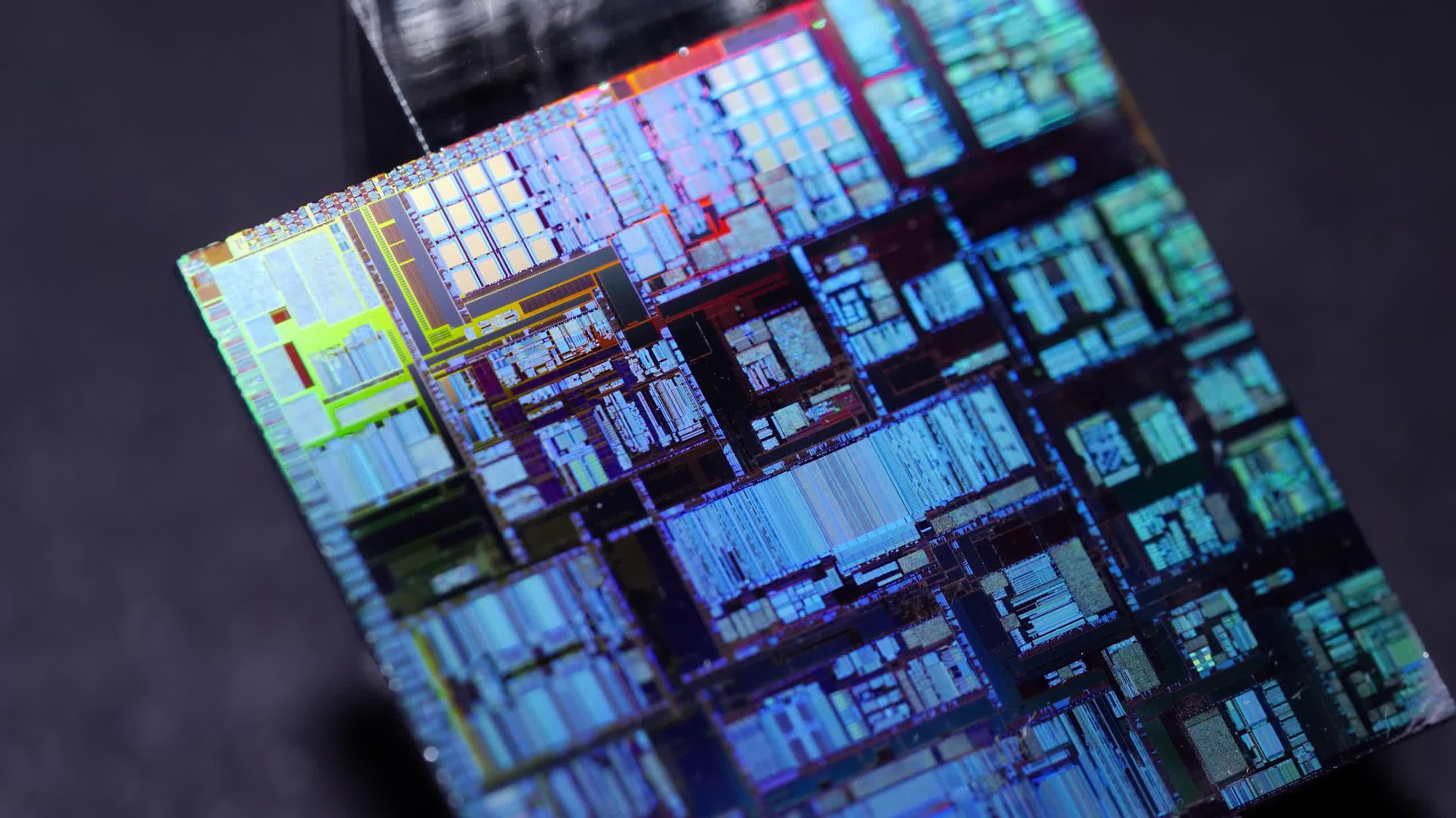

This is yet another reminder that the global semiconductor supply chain is incredibly complex yet still highly concentrated in a few countries. For instance, over 90 percent of DRAM and NAND chips are made in Taiwan, Japan, China, Singapore, and South Korea. ASML is the only company making advanced EUV lithography machines, and Tokyo Electron is the only company making EUV photoresist coater and developer systems.

Foundries like Intel, TSMC, Samsung, and others are scrambling to regionalize their manufacturing, but any potential conflict —say, in Taiwan — is a recipe for disaster. More than 63 percent of all chips are made in Taiwan and 18 percent are made in South Korea, which should give you an idea of the fragility of the global semiconductor supply chain.

Source link