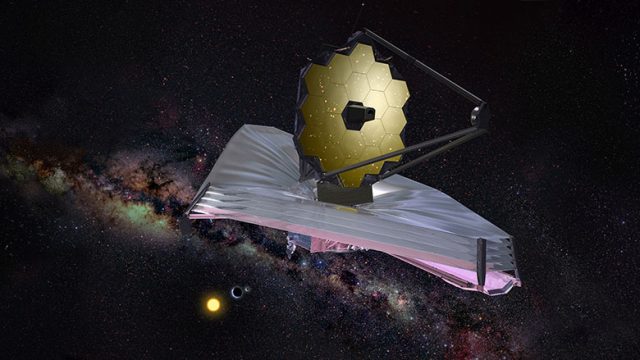

When NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was on the ground, it seemed like all we ever heard was bad news — delays, redesigns, cost overruns. Ever since the launch though, all the team’s hard work has been paying off. The launch went perfectly, the telescope has a fuel surplus, and it unfolded exactly as designed. Now, Webb has finally done the one thing telescopes are supposed to do: it detected photons.

Webb’s first light came from a star known as HD 84406, which sits in the constellation Ursa Major about 258 light years away from Earth. However, Webb didn’t “see” the star in the way you’d expect. This is just the beginning of Webb’s months-long calibration procedure, so the instruments registered 18 individual points of light, one from each mirror segment (see the simulation below). This is apparently just what NASA expected, and over time, it will be able to adjust to segments to bring the image into focus.

From the start, NASA created Webb to be more powerful than Hubble. The iconic space observatory has been operating for 30 years, and technology has come a long way since it was designed in the 1980s. Hubble’s primary mirror has a total surface area of about 48 square feet (4.5 square meters), but Webb’s mirror is 273 square feet (25 square meters). Webb is also a Korsch-style telescope with 18 individual segments. It takes time to calibrate this setup, but it’s more reliable than the Ritchey–Chrétien reflector from Hubble. That single hyperbolic mirror was a problem for Hubble, requiring a service mission to correct for an optical imperfection. That shouldn’t be a concern with Webb’s adjustable segments.

NASA chose HD 84406 as a calibration target because it’s relatively bright and in an isolated part of the sky free of other bright objects. Over the next three months, NASA will nudge each of the gold-coated beryllium panels into place, turning 18 points of light into one. JWST is also cooling its heels as NASA waits for its instruments to, well… cool off. The telescope is designed to operate in the mid-infrared, and any errant heat could ruin those observations. So the instruments need to get down to almost absolute zero. The calibration couldn’t even begin until the temperature dropped to -244 degrees Fahrenheit (-153 degrees Celsius).

Webb is orbiting the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point out past the moon’s orbit. This location allows Webb to remain stationary without using too much fuel, of which it has a limited supply. Luckily, NASA now believes Webb has enough in the tank to keep it functional for 20 years. It should return its first real images this summer.

Now Read:

Source link